Lakaba day

Lakaba Day: The Ancestral Gathering of the Oníkoyi Lineage

Lakaba Day is a sacred annual observance within the Oníkoyi dynasty, rooted in the ancient town of Ikoyi-Ilé in present-day Oyo State. Unlike public festivals such as Eyo or Egúngún,Lakaba Day is an intimate ritual of remembrance, performed to honor the royal ancestors of the Oníkoyi household — one of the oldest and most respected warrior lineages in Yorubaland.

Who Are the Oníkoyi?

The Oníkoyi is one of the four principal warlords of the Old Oyo Empire (alongside the

Aresa, Onipakala, and Ajeran), entrusted with guarding the northern territories and leading military expeditions. The dynasty traces its roots to Ojo Akinrogun, an esteemed warrior and noble loyal to the Alaafin.Lakaba Day is therefore not just a festival — it is a ritual of continuity, connecting present-day Oníkoyi descendants to centuries of militaristic honor, governance, and spiritual guardianship.

Meaning of Lakaba

The word “Lakaba” in this context connotes calling forth — summoning the spirits of the royal ancestors for blessing, counsel, and protection. It is the day when the living say:“We have not forgotten — come and dwell with us.

Ritual Features of Lakaba Day

Ancestral Invocation

The day begins with traditional rites at the royal shrine (Oju-bo Oníkoyi), where prayers, libations, and oríkì (praise poetry) are offered. Names of past Oníkoyi rulers and matriarchs are called, each remembered for bravery, wisdom, or sacrifice.Procession Within the Royal Court Unlike Egúngún which travels through the town, Lakaba remains mostly within palace grounds.Elders of different Oníkoyi branches — home and diaspora — renew bonds, settle disputes, and reaffirm lineage hierarchy

Offering to Ogun and Ancestral Deities

As a warrior house, offerings are made to Ogun, the god of iron and warfare, alongside Esu and the ancestral spirits. It is a day of spiritual cleansing and collective rebirth.

Communal Feast & Reconciliation

After prayer comes a communal feast — kola nut, palm wine, yam, goat, and traditional soup.Grievances within the family are resolved. The essence of Lakaba: unity before ancestors.

Cultural Significance

Purpose and Meaning

Remembrance:Honoring warrior ancestors of the Oníkoyi throne

Unity :Gathering of global Oníkoyi descendants

Renewal :Blessing of children, marriages, leadership

Identity :Reinforcing noble heritage within Yorùbá history

Lakaba Day is often when far-flung descendants — in Lagos, Ibadan, or overseas — return to Ikoyi-Ilé, reaffirming their bloodline to the ancient crown.

Lakaba vs Egúngún

While Egungun displays ancestral spirits to the public, Lakaba calls them privately for counsel.It is a festival of memory, not spectacle.

Preserving Lakaba in Modern Times

Today, with many Oníkoyi descendants holding significant positions, Lakaba is gaining renewed attention as a symbol of inherited leadership, dignity, and warrior discipline.Many within the dynasty now seek to document Lakaba Day for younger generations — so that nobility is not lost to modernity.In the Words of the Elders“A family that forgets its Lakaba will wander without root.

Boat Regatta

Boat Regatta in Lagos: A Royal Water Parade of Heritage and Prestige In the heart of Lagos, where the lagoon meets history, the Boat Regatta stands as one of the grandest expressions of aquatic culture, royal tradition, and coastal lineage. Often held during major festivals such as Eyo or in honor of visiting dignitaries, the Lagos Boat Regatta transforms the waters into a moving gallery of pageantry, music, and ancestral pride.

Origins of the Regatta

Rooted in the traditions of the riverine communities of Lagos, including Ikoyi, Isale Eko,Ijora, Epe, Badagry, and Ilase, the Regatta is not merely an exhibition — it is a ceremonial homage to the water deities (Olokun) and a salute to the ruling houses and quarters that historically navigated the waterways.These boat displays were historically used to welcome kings, celebrate coronations, or mark special festivals. With time, they evolved into competitive yet cultural showcases, symbolizing unity, wealth, and craftsmanship.

The Spectacle on Water

During a Regatta, the Lagos Lagoon comes alive with ornately decorated canoes, eachrepresenting a royal house, community, or lineage family. Boats are adorned with

Traditional fabrics, totems, and symbols of power

Masquerades, dancers, and drummers onboard

Acrobatic paddlers performing synchronized strokes

Royal regalia — including umbrellas, gongs, and staff of authority — are prominently featured toreflect the status of each participating group.

Cultural Significance

The Regatta is more than celebration; it is identity on water. It honors:

Ancestors who journeyed the creeks and built Lagos from the waterways

Fishermen and boatmen who sustained economies and trade

Spiritual devotion to Ọlọkun (Goddess of the Deep Sea) and river spirits

It is also a diplomatic parade — a public confirmation of peaceful coexistence among different coastal communities under the authority of the Oba of Lagos.

The Regatta and the Eyo Connection

While the Eyo Festival celebrates the spirits of the land (Ẹlẹyọ), the Boat Regatta mirrors the spirits of the waters. When both are held in the same season, land and water — Ilẹ ati Omi —come together to honor the ancestors of Lagos.

Modern Revival & Global Attention

Today, the Lagos State Government occasionally revives the Regatta for tourism and international events. It serves not only as a heritage display but as a reminder that Lagos is acity built on water — commerce, culture, and courage.

A Living Ode to the Water Warriors

Each paddle stroke signifies more than movement; it is rhythm, history, and survival. As thedrums echo across the lagoon, the Regatta declares to all who watch:“Before roads, we had waters. Before cities, we had canoes. We are children of the tides.

Eyo

Eyo: The Spirit of Lagos – A Cultural Day of Ancestry,

Elegance and Tradition

Lagos may be known today for its hustle, business and modernity, but beneath the skyscrapers

and coastal lights lies a tradition centuries deep—Eyo, the grand cultural festival of the Lagos

people. Often described as a forerunner to the Rio Carnival, the Eyo Festival is not just a

spectacle; it is a spiritual and ancestral procession rooted in honor, passage, and collective

memory.

What is Eyo?

Eyo refers to the white-clad masquerades—also called Adamu Orisha—that appear during the festival. Dressed in flowing agbada-like robes (called àgò), wide-brimmed hats (akete), and carrying a staff (opá nbatá), the Eyo masquerades represent ancestral spirits returning to bless the land. No other day in Lagos looks like Eyo Day.

Origins and Purpose

Historically, the Eyo festival is performed to:

Honor a departed Oba (king) or a prominent Lagos chief

Welcome a new Oba into the palace

Invoke blessings and peace upon the land

Eyo is not an annual festival with a fixed calendar date. It is proclaimed by the Oba of Lagos and the Iga (palace houses) when the time is significant—making every appearance rare and historic.

The Procession: A Moving Ocean of White

On Eyo Day, thousands of Eyo masquerades fill the streets, dancing from their respective familyhouses towards Idumota, finishing at Iga Idunganran, the palace of the Oba of Lagos.No shoes or sandals

No smoking, whipping, or riding horses

Women’s head ties (gele) must be tied properly

Each Eyo group (Iga) is distinguished by the color of its hat ribbons (aláàbà). The most senior is Eyo Adimu, always the first to appear. Meaning for Lagosians Eyo is not entertainment—it is heritage in motion. It connects Lagosians to:

Ancestors – The spirits believed to walk among the living that day

Community – Every indigeneship house participates

Honor & Transition – Marking royal passages, continuity, and collective pride

Families use this occasion to rekindle lineage bonds, pass down traditions and celebrate history with grace, rhythm, and profound ceremony.

Modern Recognition

Though ancient, Eyo remains a symbol of Lagos identity: It is featured in state ceremonies and anniversaries A major Eyo parade was held in 2012 to commemorate the death of Chief Yesufu Abiodun Oniru

It attracts cultural tourists and is regarded as a national heritage event

The festival is also featured on the Lagos State emblem, symbolizing the spirit of Lagos—white,noble, ancestral, and undying.

A Day When Spirits Dance

On Eyo Day, Lagos pauses. Modern life steps aside.

What remains is a city dressed in white, where drumming hearts and floating spirits walk

together in honor of those who came before—and a promise that tradition will never fade

Esho DayReviving the Ancestral Spirit of Ikoyi-ìlè

Every year, the sons and daughters of Ikoyi-llè — a historic town in Oyo State, Nigeria — once athered to celebrate Esho Day, a vibrant cultural homecoming that united Onikoyis from a round the world. Known for its deep ancestral pride and royal lineage, the festival honored the ancient Eso Ikoyi warrior class and reaffirmed the community’s connection to its noble roots.

A Festival of Legacy and Unity

Esho Day, also called Ikoyi Eso Day, is more than a celebration; it’s a living remembrance of courage, culture, and community. Traditionally, the event brought together descendants of the Ikoyi royal lineage from across Nigeria (settlements in Lagos, Kogi, Ekiti, Osun, Ondo, Kwara, Ogun, and even across Benin / Togo) and the diaspora to pay homage to their forefathers, renew family ties, and celebrate their shared heritage

The festival’s ceremonies were rich with symbolism – processions of traditional chiefs, oríki (praise chants) echoing the bravery of the Eso warriors, and drumming that carried the heartbeat of Ikoyi itself. The Onikoyi, as the spiritual and cultural leader, played a central role, receiving guests, leading prayers, and blessing the people.

A Pause in Tradition

In recent years, however, the annual festival has been on hold. The Onikoyi stool — the traditional throne of Ikoyi-ilè – remains vacant, creating a leadership gap that has stalled major cultural events like Esho Day and the Antete Festival. The palace, once alive with horses, drums, and celebration, now awaits restoration.

Community elders have appealed to the Oyo State Government for intervention to restore the throne and revive the town’s heritage. They believe that the rebirth of Esho Day would not only restore cultural pride but also stimulate local tourism and unity among koyis worldwide.

Reviving the Flame

Despite the pause, the spirit of the Esho lives on in the hearts of the people. Diaspora groups, social media communities, and cultural advocates continue to promote Ikoyi heritage, keeping the legacy of Esho Day alive.

Many hope that once the Onikoyi stool is restored, Esho Day will return stronger — as a renewed symbol of ancestral power, unity, and pride. For loyi-lle, it’s more than just a festival; it’s a reminder that heritage, like fire, may dim but never dies.

Agere

Agéré Masquerade: The Acrobat Spirit of Yoruba

Performance

Among the many ancestral masquerades of Yorubaland, the Agéré Masquerade stands apart— not for its fearsome presence, but for its grace, agility, and theatre. Known for breathtaking acrobatics, dance, and dramatic storytelling, Agéré embodies artistry, agility, and ancestral spirit.

Origin and Ancestral Significance

Agéré (Àgẹ ̀ rẹ ̀ ) originates from the traveling theatre tradition of ancient Yorubaland, often linked

with Alárìnjó performers — the earliest form of Yoruba theatre. While some masquerades evoke fear or spiritual awe, Agéré appears with elegance, entertainment, and coded wisdom.It is believed to be a messenger of the ancestors, arriving during festivals to bless the community with joy, movement, and lessons disguised in performance.

Appearance and Costume

Agéré is easily recognized:

Face covered with a carved wooden mask or cloth veil

Costume sewn in bright layers, enabling flexibility

Often carries a staff or props used in dramatic acts Sometimes painted or decorated like a court jester, symbolizing both wisdom and comic relief Unlike warrior masquerades, Agéré’s identity is defined by movement, not intimidation.

Performance Style: Dance, Acrobatics & Drama

Agéré is the heartbeat of the arena — spinning, somersaulting, climbing, miming, and engaging the audience with mimicry or satire.Its appearances traditionally include:

Flips and somersaults

Mock fights or playful chasing

Dramatic sketches reflecting moral lessons

Interaction with drummers and chanters — responding to Bata or Gangan talking drums. Every step of Agéré is a dialogue between performer and drum, between spirit and community.Cultural Role and Celebration Agéré performs at:

Community festivals

Coronations & royal celebrations

Eyo Day and other Lagos–Oyo cultural displays

Funeral rites of chiefs or titled figures

While it entertains, Agéré also conveys social commentary — mocking pride, praising humility,

reminding the community of ancestral ethics.

Symbolism of Agéré

Symbol Meaning

Agility & Flight Spirit’s freedom beyond human limit

Comedy & Satire Hidden wisdom in laughter

Disguise No man is above ancestral judgment

Dance Celebration of life’s movement

Agéré: Theatre Before Theatre

Long before modern Nollywood or stage drama, there was Agéré — carrying stories on its feet, teaching lessons through acrobatics, and preserving Yoruba creativity through motion. To witness Agéré is to witness the living breath of Yoruba culture — ancestral but ever-alive

Igunuko

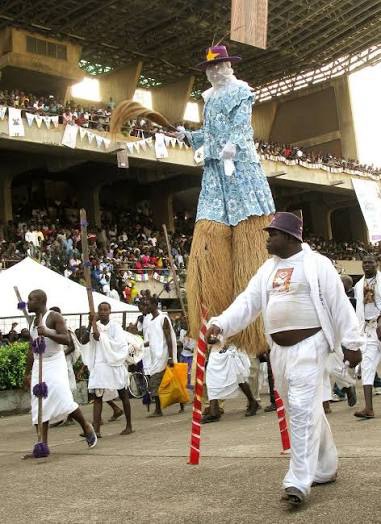

IGUNNUKO: The Towering Spirit of Heritage in Yorùbá–Nupe Culture

Among the many masquerade traditions of southwestern Nigeria, none commands presence and mystique like Igunnuko— the towering spirit figure known for its imposing height, hypnotic movement, and sacred authority. Rooted in Nupe origins and intricately woven into Yorùbá cultural life, particularly in Lagos Division and Ikorodu, the Igunnuko masquerade stands today as both a spiritual guardian and a living monument of ancestral continuity.

Origins: From Nupe Heartland to Lagos Shores

Historically traced to Pategi in present-day Niger State, Igunnuko is believed to have migrated

into Yorùbá territories in the early 19th century. Oral history tells of a Nupe priest,often named Yaisa Ayani, who brought the cultic knowledge to Lagos around 1805–1814. From there, it established strongholds in old Lagos settlements such as Epetedo, Isolo, Okokomaiko, and Ikorodu, where shrines known as Igbo-Igunnu (Igunnu Grove) became centers of worship and initiation.

A Masquerade Unlike Any Other

Igunnuko is instantly recognizable — not by mask alone, but by stature. It is one of the tallest masquerades in West Africa, rising above rooftops on hidden stilts or tiered platforms. Draped in voluminous fabrics that ripple with each movement, Igunnuko appears not as a dancer but as a slow-moving spirit, towering, silent, and commanding reverence. Its presence is accompanied by an entourage of drummers, chanters, and devotees who announce its arrival with coded praise chants and deep bata rhythms.

Ritual Significance: Oracle, Protector, Ancestral Envoy

More than spectacle, Igunnuko is believed to be an oracle-spirit, consulted for protection,prosperity, fertility, and communal healing. Elders speak of its ability to “see what is hidden”— ajudge of truth and a destroyer of malevolent forces. During festivals, it visits family compounds,blessing households, settling disputes, and reaffirming moral order.

A central ritual in the festival is the Kuso Ceremony — the uprooting and dragging of a sacred tree. The tree’s journey through the community symbolizes spiritual cleansing, the removal of misfortune, and ancestral presence rooted in the land.

The Festival Cycle: Reunion of Lineage and Spirit

In places like Ikorodu and Okokomaiko, the Igunnuko Festival spans days — sometimes 14 to 17 — involving shrine vigils, restricted rites for initiates, and the final public procession. Thesefestivals draw families from far and wide, as lineage members return home to honor ancestral bonds. For many, it is a cultural homecoming — a time when the living commune with those who walked before them.

Symbol of Identity in Modern Lagos

Despite urban transformation and the pressures of modern religion, Igunnuko endures. It has become a marker of identity for old Lagos families of Nupe-Yorùbá descent and a cultural emblem that attracts researchers, photographers, tourists, and heritage custodians. Today, clips of Igunnuko parades circulate on digital platforms, prompting a new generation to rediscover its significance.

Challenges and Preservation

Yet this tradition stands at a critical threshold. Urban migration, reduced initiation into the cult,and misunderstanding of masquerade spirituality threaten its continuity. Without documentation,younger generations risk inheriting fragments of a once-whole legacy.

Cultural advocates and local custodians now call for:

Archival Documentation

Cultural Policy Support from Lagos State

Educational Integration as Heritage, not Myth

A Living Legacy, Not a Lost Relic

Igunnuko is not merely a costume. It is a living archive — carrying the voices of Nupe migration,Yorùbá adaptation, ancestral law, ritual healing, and community identity. To witness Igunnuko is to witness a dialogue between the seen and unseen, between memory and presence.In its towering silence, it reminds every observer:We are never taller than when we stand on the shoulders of our ancestors